The 1996 Mount Everest Disaster is one of the most deadly, haunting disasters in the history of high-altitude climbing and mountaineering. The wind howls. It was hard to breathe and climbers were just meters away from the summit of Mount Everest, when an unanticipated storm threw them into chaos.

In the span of a few hours eight climbers were dead and a handful more were left stranded in the awful "death zone". What makes a disturbing situation even more disturbing is that these climbers were mainly experienced climbers, many of whom were led by some of the world's best mountain guides.

The 1996 Everest Disaster shocked the climbing community. How could numerous accomplished climbers all succumb on the same day?

The poor decision-making of the summit party members, poor timing of their summit attempt, lodged a log jam of people on the mountain, and changing weather brought on a larger discussion surrounding the commercialization of Everest, the ethics behind climbing and guiding, and climbing protocols for high-altitude climbs.

This was not just an accident; it was a catastrophe that changed the way people think about Everest. Survivors have relayed the experience in books and documentaries, and have in turn maintained the memory of that day in the storefronts of bookstores and video shops.

Even now, nearly 25 years later, the 1996 disaster will always remind us that Everest and everything it stands for deserve the respect and humility it commands, and much like history in general, will always serve as a very dark day in mountaineering history.

What was the 1996 Mount Everest Disaster?

The tragedy of May 10 and 11, 1996, involved the death of 8 climbers during a mass ascent/descent to the summit of Mount Everest during the 1996 Mount Everest disaster' .

A number of guided expeditions participated in the mass ascent, particularly Rob Hall Adventure Consultants led by Hall himself and Scott Fischer's Mountain Madness also led by Fischer with Fischer's group summiting earlier than Hall's group.

Due to a sudden and violent storm that brought winds exceeding 25ft/s (8m/s, or greater than 100 mi/hr (160 km/hr)) with whiteout conditions both Hall and Fischer found themselves, along with their climbers stranded high on the mountain.

Many of the climbers found themselves with nowhere to retreat to; inherent delay in preparing and climbing, congestion in the most ideal passageways, and lack of decent logistics, left climbers exposed to the regrowth of frost, fatigue, and low oxygen for altitude - death zone (above 8,000 meters).

As dreadful as the total deaths were and many of the deceased were experienced climbers led by world class mountain guides the concerning portion was that both climbers were with Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, both experienced climbers, however the delays lead to a bad situation being made worst, at the summit; where they were were peering over a very narrow ridge and even if they had only left to contend with the "traffic", the fixed ropes were misplaced, whereby the fixed ropes contributed to their deaths. They also reached the summit late afternoon and did not turn around at their predetermined time, were faced with gale force winds, and the temperatures could have easily fallen to -40 degrees Celsius.

The tragedy shocked the world and sparked a very long and heated discussion about the commercialisation of Everest and "summit fever", ambition trumping safety.

Into Thin Air (1997) was Jon Krakauer, a survivor who recorded the disaster, which also brought out counter-narratives like Anatoli Boukreev’s The Climb, and has been going on a debate within the mountaineering community ever since.

Later on, a weather analysis showed that the jet-stream over Everest shifted suddenly, which resulted in oxygen levels dropping by 14%—a very lethal impact to already tired climbers.

The death of 1996 still looms over the history of Mount Everest as the blackest day that changed the entire climbing community, as well as the companies, forever after the tragedy.

Who died in the 1996 Mount Everest Disaster?

In the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, 8 of the 19 members of the two leading commercial expeditions, Adventure Consultants and Mountain Madness, were climbers who died on May 10 - 11. An overall 12 deaths occurred during the climbing season; however, the 8 deaths were shocking world news relating to the 1996 Mt. Everest disaster.

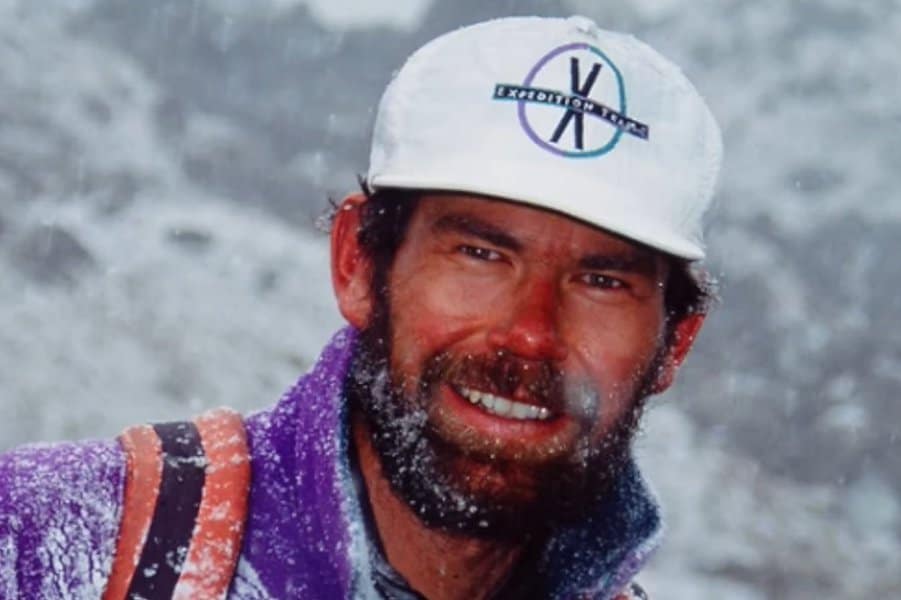

Rob Hall

Rob Hall was a well-known mountaineer from New Zealand and the leader of the Adventure Consultants team. Hall was killed when he was at approximately 8,749 meters (28,704 ft) on May 11 1996 at the age of 35, at high altitude on Mount Everest near the South Summit.

Hall did not abandon Doug Hansen, who could not move during a storm. Hall survived two nights at extreme altitude. Ultimately Hall was killed by exposure and could not descend. His body is still on the mountain, quite close to where he died.

Doug Hansen

Doug Hansen, an American climber and a client of Adventure Consultants, died on his descent near the South Summit of Everest at age 46. Hansen became spent, hypoxic, and was trapped by the blizzard along with Rob Hall. Doug Hansen's body was never found, but it is presumed that he fell on the upper slopes during the storm of May 10-11.

Yasuko Namba

Yasuko Namba, at 47, was a skilled Japanese climber who was the oldest woman to summit Everest till 2012. Yasuko was also a member of the adventure consultants' climbing team. She made it to the summit, but shortly after, she was too tired to be able to continue her descent. Yasuko died on the descent between Camp IV (South Col, approx.8,000m) and died of hypothermia during the storm. Yasuko's body was discovered the next day by the other climbers.

Andy Harris

Andy Harris (31) was a New Zealand guide who worked for Adventure Consultants. The exact circumstances of what happened to Andy Harris are unrecorded. He may have died high on Everest, either near or below the South Summit ridge. Andy was last observed trying to assist Hall and Hansen; he was never seen again. Nothing of Andy Harris was ever found. Andy Harris died of hypoxia, or exposure, or perhaps a fall, on the night of the storm.

Scott Fischer

Scott Fischer was a very experienced climber and a professional mountaineer from the expedition company Mountain Madness. The day of May 11, he became very tired and exposed to cold at about 8300m (27,230 ft) on Southeast Ridge. Fischer was suffering from altitude sickness and exhaustion could not reach safety after the storm. He was eventually found by 2 other guides on the mountain.

Tsewang Samanla

Subedar Tsewang Samanla, one of the three Indian climbers from the Indo-Tibetan Border Police team, lost his life on the Northeast Ridge of Everest at about 8600m (28,215 ft). Samantha and the other climbers were caught by the storm when they came down from the summit after their summit attempt. Let us say that I will offer a body of Samanla, which was found near their last revealed place after the search.

Dorje Morup

Lance Naik Dorje Morup, belonging to the Indo-Tibetan Border Police as well, lost his life together with his co-workers when they were descending the Northeast Ridge at extreme altitude. His body has not been found and therefore he is presumed dead, having died from exhaustion, exposure, and during the strong storm.

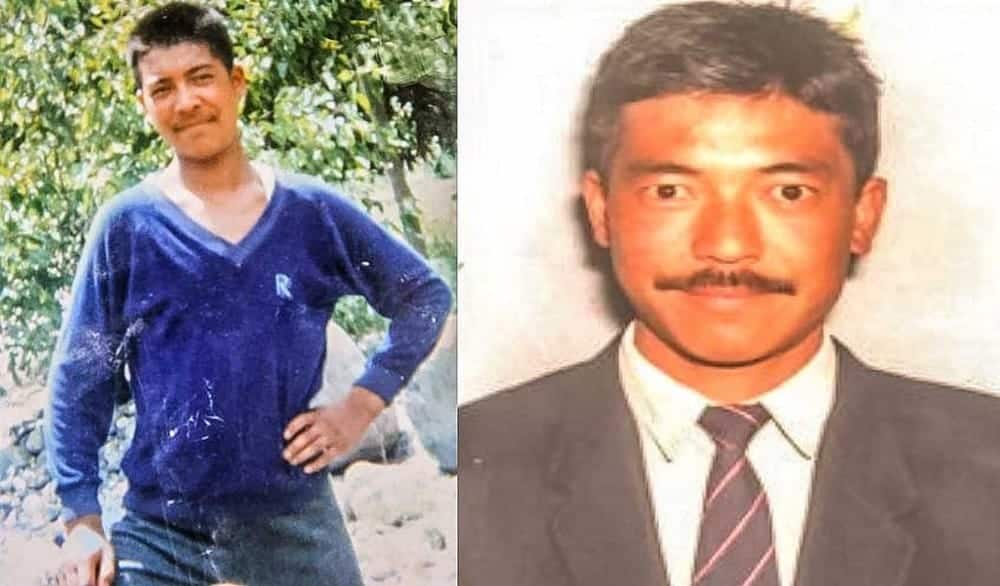

Tsewang Paljor ("Green Boots")

Head Constable Tsewang Paljor, age 28, was the third member of the Indian team who lost his life on the Northeast Ridge. At the time of finding, he was the third corpse; nevertheless, he died earlier than the other two. He is easily identified by the green shoes that were with him at the place of the remains in a limestone cave at around 8,500 m (27,887 ft), which is a well-known spot that "Green Boots' Cave" is now called. It is thought that he has died due to the storm and a lack of oxygen. He is the most famous victim on Everest and the most disturbing sign for Climbers approaching the North Col route.

1996 Mount Everest Disaster Survivors Names and Where are They Now

Eight climbers passed away on the mountain, leaving 25 surviving climbers from a total of 33 climbers caught in the storm during the May 10–11, 1996 Margaret Everest disaster.

The remaining climbers involved in the incident included guides, clients, helio, and Sherpas—all descended alive; mostly with a lot of frostbite, tiredness, and residual effects of longevity (exposure, altitude). The stories of the survivors tell of hope, resilience, resourcefulness, and at times caprice, in ungainly, troublesome situations. Some of those surviving climbers are:

Beck Weathers

Beck Weathers, M.D., an American pathologist, survived a lonely night on the mountain near Camp IV after twice being left for dead in a blizzard while suffering from severe frostbite and hypothermia. Dr. Weathers somehow regained a state of consciousness, got to his feet, and walked, unaided, back to his camp.

A few hours later, he was rescued by helicopter in what is, to date, one of the highest helicopter rescue missions completed. Dr. Weathers later became a motivational speaker as part of his survival message. Beck Wheders is still residing in Texas, and continues to inspire people with his story. Today, he remains with only his right hand and a few fingers on his left hand, nose, and the rest of his face left intact from frostbite.

Jon Krakauer

Jon Krakauer, the journalist and also a client of Adventure Consultants, escaped Everest by descending and summiting (on 10 May) quickly enough after the storm was too severe to impact his summit. After he returned home, Krakauer wrote and published a best-selling book (Into Thin Air) that brought the world’s interest in the tragedy to a level never before imagined. He continues to write books and articles, having a career that includes writing and investigating climbing and outdoor topics.

Anatoli Boukreev

Anatoli Boukreev (Russian-Kazakh climber and guide with Mountain Madness) was a noted high-altitude climber who was certainly an important player in the rescue, and went out alone at night multiple times in search of climbers stranded and people in trouble. Boukreev survived through his conditioning, acclimatization, and absolute refusal to use supplemental oxygen, and he found enough capabilities to save others. Following the tragedy on Everest, Boukreev continued to guide and climb until his death in an avalanche at Annapurna in 1997.

Charlotte Fox

Charlotte Fox, a Mountain Madness client, made it out alive after being stuck in the storm atop the mountain. Fox and a group of climbers descended in a group through the whiteout, suffering frostbite, but made it back to safety. After Everest, she returned to Colorado. Fox continued to be active in mountaineering for many years, and sadly died in 2018 in a fall in her home.

Sandy Pittman

Sandy was an American climber and socialite. She was a member of the Mountain Madness expedition and survived after being helped down by guides and teammates in the storm. When she returned home, she returned to her work as a journalist, relived the Everest experience numerous times in publications and in various interviews, and lived an active life.

Tim Madsen

Tim Madsen was an Adventure Consultants client and has gone public regarding his accounts and survival experience after overcoming a traumatic night on the South Col as he stood up and said he could not leave his friends in peril. Tim was able to return home and went public with his accounts and survival experience.

Neal Beidleman

Guide Neal Beidleman with Mountain Madness, was successful in moving an array of climbers, most of whom were disoriented or incapable of taking care of themselves, out of Camp IV to Camp I, a distance from Camp I during the storm. He still integrates with the community of climbers and engineers and very regularly talks and promotes safe practices of mountaineering and his experience on Mt. Everest.

Mike Groom

Mike Groom, the Australian guide, worked for Adventure Consultants, gathered the remaining climbers, and helped them descend from Camp IV in what he planned to be the most dangerous segment of the climb. Mike kept climbing until he retired, but many people connect Mike to what he did as the disaster unfolded.

Stuart Hutchison

Canadian client Stuart Hutchison gave up near the summit, thus likely saving his life. Stuart helped to search for their missing climbers at Camp IV and, later, returned to Canada to resume his profession as a medical doctor, sometimes adding a perspective to the topic of Everest and climbing ethical issues.

Who Was to Blame for the 1996 Everest Disaster?

The tragic 1996 Everest disaster was caused by a long chain of leadership and logistics failures; expedition leaders Rob Hall (Adventure Consultants) and Scott Fischer (Mountain Madness) ignored the weather, their own stated turnaround time of 2:00 PM, and went up in a storm (all of which were exacerbated by the pressures of competition and previous commitments to the media, including the assignment for Jon Krakauer).

They experienced bottlenecks on the Hillary Step, both through crowding and also missing fixed ropes, and not only wasted time, but wasted time that they couldn't afford.

Overconfidence and groupthink also clouded their critically important decision-making; Hall had summited Everest 4 times prior to this attempt, and Fischer's competition offered contemporary low-risk cues, contributing to his group's underestimating the risks.

Jon Krakauer took criticisms of commercialising Everest a step further, as he argued recognising the competition of other qualified climbers allowed guides to help those who were underqualified reach the summit with bottled oxygen, as it lowered a safety bar and facilitated the rest of the risk-taking climbers.

Communication failures played an important part in that faulty radios, the Sherpas were disorganized, and many climbers were abandoned due to the inability to establish a chain of command.

Reddit posters mostly laid the blame on the expedition leaders—Hall and Fischer—for their irresponsible leadership styles, competitive motivations, and failure to safely implement any standard travel protocol, prior to problems with logistics, decision-making, crowding, and oxygen at extreme altitude.

Hall was widely admired for his professionalism, experience, and dedication, even though he completely failed as a leader. He insisted on staying to attempt to help his struggling client rather than attempting to ensure his survival. Hall might be described as being at least partially at fault, but not necessarily fully responsible, because of the other bad systemic dynamics, logistical issues, and poor decision-making.

Adventure Consultants and The 1996 Mount Everest Disaster

Adventure Consultants was originally Hall & Ball Adventure Consultants. In 1991, two elite New Zealand mountaineers, Rob Hall and Gary Ball, founded the company. Not to be outdone, not only did they achieve the Seven Summits in seven months, but they also looked into developing guiding operations for Mount Everest.

After Ball's death in 1993, Hall was the one who ran the company. By spring 1996, Hall had personally guided 39 clients to the Everest summit.

The Tragedy of May 10–11, 1996

The final summit attempt, which actually took place from Camp IV on May 10–11, 1996, was when Hall's Adventure Consultants team joined others—the teams under Mountain Madness, for example. The situation was quite different as Hillary Step faced delays, the fateful time of 2 p.m. for turnaround was violated, and a change of weather brought on a blizzard at high altitude.

Eight climbers lost their lives that night, among them were Hall, guide Andy Harris, and clients Doug Hansen and Yasuko Namba. Hall was there with Hansen until the very end; therefore, he died trying to save a life.

Recovery, Restructuring, and Continued Operations

After Guy Cotter took over the leadership of Adventure Consultants, he did not waste any time and went on to drive a very successful Cho Oyu expedition in the latter part of 1996. The company had 19 Everest expeditions under his

The company stays true to a core philosophy of small guided groups, high guide-to-client ratios, and excellent training, logistics, and environmental stewardship standards.

Current Status

Adventure Consultants is still in the business of providing adventure holidays and conducting training in mountaineering and rock climbing all over the world, including the Himalayas, the Seven Summits, Antarctica, Europe, etc.

The company is also engaged in conducting guided Everest expeditions, but now they place more emphasis on the quality, safety, and sustainability aspects of the journey.

What Actually Happened on the Night of May 10–11 1996 Mount Everest Disaster?

May 10, 1996 (Nightfall into Early May 11)

00:00–01:00: Summit Push Begins

Rob Hall’s Adventure Consultants expedition and Scott Fischer’s Mountain Madness team set out from Camp IV (South Col) for the summit attempt. Along with them, there were the Taiwanese group and an Indo-Tibetan Border Police expedition.

05:30 AM: Bottlenecks and Delays

At the Balcony (~8,350 m), ropes that were to be fixed were not there, so climbers had to wait. A second major hold-up occurred at the Hillary Step (~8,760 m). While guides were putting ropes, congestion from roughly 33 climbers kept them from reaching the goal.

13:07 PM: Boukreev Summits Early

Mountain Madness guide Anatoli Boukreev arrives at the summit (without oxygen) and starts descent after giving assistance to those who need it at around 14:30.

14:00–15:45: Climbers Reach Summit Late

Many climbers, among them Hall’s clients (such as Jon Krakauer, Andy Harris, Yasuko Namba, Doug Hansen) and Fischer himself, reached the peak much later than the safe turnaround time of 2:00 pm. Fischer summit at about 15:45.

15:00 pm: Snow Begins Falling

At the beginning of snowfall and dimming daylight, Hall, near Hillary Step, meets client Doug Hansen, who, although lacking in oxygen, refuses to go down. Hansen is going to be with Hall, who decides to stay with him and also orders the Sherpas to help other climbers and to place oxygen canisters on the way.

5:30–6:00 pm: Blizzard Hits

The storm overpowers the South Col route and transforms into hurricane-force wind (~70 mph) and snow, thus blinding. Descending climbers lose the fixed rope.

Night of May 10 (20:00–00:00 approx)

Groups such as guides Mike Groom with clients Beck Weathers and Yasuko Namba, as well as Mountain Madness members, are straining in the storm near the South Col. Some become immobilized and exhausted, and dark attempts to find Camp IV prove to be futile. Beck develops hypothermia; Namba still insists that oxygen has to be given even though the supply is depleted.

May 11, 1996 (Early Morning Hours)

~04:45 AM: Radio from Rob Hall

Via the radio, Hall reports to Everest Base Camp: Andy Harris had reached his position, but now he was gone, and "Doug is gone." At some point during the night, his oxygen regulator froze. In the morning, after regaining function, he was not able to descend because of the frostbite on his hands and feet. Near 09:00 AM, he asked Base Camp to call his wife, saying, "Sleep well … Please don't worry too much." These were his last known words before dying at or near the South Summit.

~06:00 AM: Harris Missing

Base Camp learns that Andy Harris, who had left for a rescue mission to aid Hall and Hansen, is now missing and presumed dead.

~07:30 AM: Survivors Found

Jon Krakauer and others locate Yasuko Namba and Beck Weathers close to death near the South Col. They are severely frostbitten and disoriented.

Midday, May 11: Rescue & Casualties Confirmed

The rescue mission continues with added vigor as the weather improves. The deaths of eight climbers during the night and early morning are now certain: Hall, Fischer, Harris, Hansen, Namba, plus three members of the ITBP expedition (Tsewang Samanla, Dorje Morup, Tsewang Paljor).

1996 Everest Disaster Death List

| Name | Role | Status (May 10-11, 1996) |

| Rob Hall | Guide/Leader | Died (Exposure) |

| Andy Harris | Guide | Died (Presumed, exposure/fall) |

| Doug Hansen | Client | Died (Presumed, exposure/fall) |

| Yasuko Namba | Client | Died (Exposure) |

| Mike Groom | Guide | Survived |

| Jon Krakauer | Client/Journalist | Survived |

| Beck Weathers | Client | Survived |

| Stuart Hutchinson | Client | Survived |

| Lou Kasischke | Client | Survived |

| Frank Fischbeck | Client | Survived |

| Ang Dorje Sherpa | Sirdar (Sherpa) | Survived |

| Other Sherpas (multiple) | Sherpa Staff | Survived |

Mountain Madness (Scott Fischer, Leader)

| Name | Role | Status (May 10-11, 1996) |

| Scott Fischer | Guide/Leader | Died |

| Neal Beidleman | Guide | Survived |

| Anatoli Boukreev | Guide | Survived |

| Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa | Sirdar (Sherpa) | Survived |

| Sandy Pittman | Client | Survived |

| Charlotte Fox | Client | Survived |

| Tim Madsen | Client | Survived |

| Pete Schoening | Client | Survived |

| Gammelgaard Lene | Client | Survived |

| Martin Adams | Client | Survived |

| Klev Schoening | Client | Survived |

| Sherpa Team (others) | Sherpa Staff | Survived |

Indo-Tibetan Border Police (North Ridge Attempt)

| Name | Role | tatus (May 10–11, 1996) |

| Tsewang Samanla | Policeman | Died (Exposure) |

| Dorje Morup | Policeman | Died (Exposure) |

| Tsewang Paljor (Green Boot) | Policeman | Died (Exposure) |

| Subedar Chhewang S. | Policeman | Survived |

| Kumar | Policeman | Survived |

Taiwanese Team (Makalu Gau Ming-Ho, Leader)

| Name | Role | Status (May 10–11, 1996) |

| Makalu Gau Ming-Ho | Leader | Survived (severe frostbite) |

| Chen Yu-Nan | Team Member | Died (before main storm, illness) |

| Others (unlisted) | Team Member | Survived |

Who was to blame for the 1996 Everest disaster, as per Wikipedia?

According to Wikipedia, the 1996 Mount Everest disaster can't be attributed to a single person, because it was a result of many factors. Some of the larger factors contributing to the disaster included:

Ineffective leadership: expedition leaders Rob Hall and Scott Fischer pushed their clients to the top of Mt. Everest despite poor weather reports, and that a massive front was coming in and a snowstorm was inevitable."

Commercial pressure and competition: there was competition among guiding companies that provided direct incentives for ignoring turnaround times, and then many of those pressures led to delays and risks on summit day. Jon Krakauer, a journalist who was on Hall's team, noted that Hall took what others considered an uncharacteristic risk, and maybe because the news media had a full client complement.

Bottlenecks on the mountain: As they delayed fixing the Balcony and Hillary Step fixed ropes, and, without warning, there were so many climbers ascending at the same time that it caused delays of up to an hour and additional exposure.

Safety turnaround time ignored: Leaders allowed people to summit well after 14:00, the safety turnaround time, with some climbers summiting after 14:30, even with weather warnings being issued, thereby increasing their vulnerability to the weather.

Not enough oxygen and medical emergencies: Some climbers were experiencing drastic oxygen deprivation, and altitude illness, and experienced compromised decision-making and would then not be able to complete a rescue.

Are There any 1996 Mount Everest Disaster videos Available?

Certainly, there are a number of videos and films that cover the 1996 Everest disaster, but no real 1996 Mount Everest Disaster Videos exist. However, there are legitimate documentary footage and survivor interviews, and more dramatized portrayals intended for a wider audience.

These documentaries utilize documentary film footage made during the expedition before and after the deadly storm, and were really reflective documentary film footage, and not real-time disaster footage. As of today, there is no verified summit-day footage that portrays the unfolding crisis publicly.

However, the Netflix PBS Frontline documentary, entitled "Storm Over Everest" (2008), directed by David Breashears, as he was climbing during the event, has had some survivors and analysis, and also portrayed the tragedy as a first-hand account.

Some documentaries also include interviews of survivors and rescuers, and have been acclaimed as a legitimate and insightful documentary.

There are several dramatizations, including:

- Into Thin Air: Death on Everest (1997) is a TV movie adapted from Jon Krakauer's memoir.

- Everest (2015), a feature film adapted from the events that took place, from the audio and survivors' accounts.

- IMAX Everest (1998), (also referred to as simply Everest), included some clips from the storm that were filmed by David Breashears and his IMAX team (including their documentary, which shows some assistance on the mountain - i.e., Da Djes twins and Diego Soto).

Outside of the theatrics, there are also many YouTube clips and videos, including many compilations, survivor stories, and some that provide commentary about the survivor experiences, and what may have led up to the disaster (some of the God awful, sad ones are hours long). Many of these include survivor interviews and rely on survivor (published) accounts, including Krakauer's Into Thin Air.

So yes, here are many documentaries, and narrative films - PBS had Storm Over Everest - but we have not found or verified any footage online that actually depicts the experience that was had on the day in question, which is mildly unbelievable; to be clear, the videos, clips, and documentaries are retrospective and interpretative.

Lessons to be Learned from the 1996 Mount Everest Disaster

- Implement strict turnaround times (e.g., 1 pm/2 pm) that must be adhered to no matter how close climbers are to the summit—this is a safer way to avoid getting caught in a bad weather situation.

- Minimize congestion by setting ropes early and coordinating ascent times—stopping at narrow places such as the Hillary Step not only wastes oxygen and energy but also reduces the time of the climb.

- Focus on weather observation and take decisions in accordance with the forecast—1996 teams were not able to recognize a coming storm and thus went up in an uncertain period.

- Conduct thorough screening and training of climbers—set the minimum requirements for the experience of presence of altitude, physical fitness level, and technical preparedness so as to eliminate any risks that may arise from the presence of inexperienced clients.

- Bring surplus oxygen and instruct self-switching—current teams are always prepared with emergency reserves, and make sure that clients know the process of managing their systems in case the guides are not accessible.

- Communicate efficiently through practical tools such as satellite phones, radios, and GPS beacons—these devices are now standard for communication and thus facilitate coordination even at the worst of times.

- Build team culture with openness for dissent and psychological safety—improve members’ comfort and encourage them to share doubts or questions instead of blindly following the decisions of the guide.

- Watch out for cognitive biases that can influence decision-making, e.g., sunk-cost mentality or competition between guides—leaders should understand their responsibility and refrain from actions that get them into unsafe situations because of pressure to reach the summit.